What had I ever done to deserve this? Other detectives get the Maltese Falcon. I get a paranoid rabbit.

Ok, technically, I’m cheating here. Who Framed Roger Rabbit, the next up in the Disney lineup, is not exactly a Disney animated classic film—it’s a Steven Spielberg production, and it’s not even fully animated. But it does have a text source, unlike some of the films actually in the Disney Animated Classics collection, and it did, as we’ll see, have a tremendous impact on Disney animation, even if most of the animated bits were not done by Disney animators.

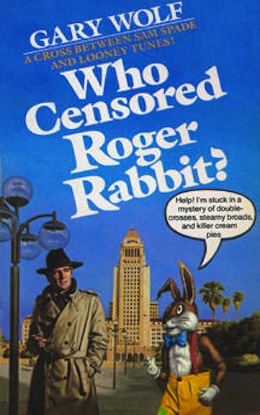

We’ll get there. First, a bit about the book that inspired the film.

Gary K. Wolf later said that he got the initial idea for Who Censored Roger Rabbit? from watching cereal commercials where cartoons interacted with kids, with everyone involved thinking this was normal. This in turn led him to create a world where Toons—from comic books and syndicates—are alive, interacting with real humans, working, signing contracts, having bank accounts. With some clear differences: most of the Toons speak in speech balloons—not just a clever nod to comic books and newspaper strips, but an actual clue in the mystery that follows. And Toons have the ability to create dopplegangers—second selves that can be used in certain high risk stunt scenes.

And, well, they’re Toons.

A few Toons—like Jessica Rabbit—do live on the uneasy border between human and Toon; they can speak normally or in speech balloons, and enter into relationships with humans, and by relationships, I mean the sexual kind. Most Toons, however, are animals, and even those that aren’t are stuck in a single form that never ages—like Baby Hermann, who complains that he has the mind and desires of a thirty year old imprisoned in the body of a toddler. Possibly as a result, although the two groups are more or less integrated, in the sense of living in some of the same neighborhoods and occasionally working together, they also use different services—one set of cops for Toons, one set for humans, for instance.

Wolf occasionally seems to be using some of this as a metaphor for racism, especially when issues of housing, marriage and immigration come up. Generally speaking, Toons are considered second class citizens, even though some of the legal barriers—with housing, for instance—have fallen, to the annoyance of some humans. The metaphor doesn’t always work, partly because it’s sometimes inconsistent—with the housing, for instance, several Toons are living in mansions with human servants—but mostly because the differences between Toons and humans go much deeper than skin color. The characters—Toon and human alike—call Roger Rabbit a rabbit because, well, he is a rabbit, even if he is at one point clever enough to play another animal entirely in Alice in Wonderland. Toons have abilities humans simply don’t have, and can be affected by things—I need to be vague here for those who haven’t read the book yet—that don’t affect humans.

And—in an issue completely skirted by the text—it’s not at all clear how Toons got here. At one point, the text talks about Toons being brought over from China to do hard labor, and a few other bits here and there suggest that Toons have been around for centuries—certainly before the newspaper strips that employ most of them now. So did they form from a few doodles on ancient scrolls, or the more elaborate images that limn medieval manuscripts? I ask, because at another point, Jessica Rabbit repeats her line that she’s not bad, she’s just drawn that way—suggesting that yes, these living Toons are fundamentally still just drawings created by humans. Does that make them equal to, or perhaps even greater than, their human creators? How do you judge a Bugs Bunny, for instance, who is name dropped in the text? He plays the bunny in Alice in Wonderland. A Dick Tracy, who despite merely acting—that is, pretending to be a cop—a cartoon pretending to be a cop—has a large fanbase of cops? And what about the hints that Toons and humans can, well, procreate—even if the Toons are entirely flat images, and humans are three dimensional?

None of these are issues Wolf tries to get into. Instead, with the occasional side glance at issues like art forgery, pornography, bad labor contracts, and police issues, he focuses on the problems of one Roger Rabbit. Roger is a very sad rabbit. Just a short time ago, he was a happy rabbit, with a beautiful and devoted wife, a steady job—if one with second billing—and the hopes of landing his very own strip. Unfortunately, it all seems to be coming apart, and Roger is convinced—convinced—that someone is out to get him and/or kill him. So Roger hires private eye Eddie Valiant—a human who needs any job he can get—to find out what, exactly, is going on.

Pretty much everyone who knows Roger Rabbit is very sure about what’s going on. As a cartoon beaver with a real medical diploma from Toon Christian University explains:

“…In my opinion, Roger must be considered a very sick rabbit, fully capable of concocting the most fantastic stories to rationalize his failures in life.”

It seems a clear cut case, until:

No doubt about it. Roger had gone to bunny heaven.

And with that, armed pretty much only with determination and Roger Rabbit’s last words, preserved in a word balloon, Eddie is off to investigate not only who killed Roger Rabbit—but also who killed his human boss, Rocco, and exactly what is happening in the seedier areas of town. Also, Toon pornography.

According to Wolf, Who Censored Roger Rabbit was rejected 110 times before finally finding a small press publisher. Publishers reportedly told him that the book was “too esoteric. Too weird” and that “Nobody would understand it.” There’s a certain truth to this—nearly every page has at least three or four comic references, sometimes more, and a few of these references are obscure indeed. Wolf can possibly be faulted for not really answering the question of “where do Toons come from?” but he certainly can’t be faulted on his newspaper comic knowledge, which ranges everywhere from superheroes to obscure soap opera comics to the funnies to, yes, Disney. It’s almost obsessive, but that helps make it work.

I also have to agree with the “weird” bit—as I noted, quite a lot here never gets explained, and Wolf throws in various oddities and jokes that make it even weirder—for instance, the way Eddie carefully collects exclamation points from shattered word balloons to sell them to publishers, or the way light bulbs appear in various thought balloons, which leads to even more questions—did candles appear over the heads of Toons in medieval times, and if Toons aren’t careful, do their thoughts get read by other people? And the Toons who, like Jessica Rabbit, border on the edge between Toon and human, aren’t just weird, but almost creepy. And there’s an occasional disconnect in tone, probably to expected in a noir novel featuring living cartoon characters. The pornography subplot is also, well, let’s go with odd.

But I don’t think any of this was why the book had difficulties finding a publisher: rather, I think the main problem was probably the lack of likeable characters. Nearly everyone in the book ends up being awful at one point or another—including people barely on the page. This is straight from the noir tradition that the novel is working with, so it’s more a feature, not a bug—but it’s a feature that might bug some readers, especially in the days before the film came out.

Nor can I agree that nobody would understand it. It has a twisted plot, yes—it’s a murder mystery—but Wolf carefully sets each and every clue in place for the denouement, which might surprise some readers, but hardly comes out of nowhere. Many of the jokes and references may be obscure, but others aren’t. And quite a few bits are flat out hilarious.

Disney, at least, liked it enough to pick up film rights while it was still in proof stage. It took another seven years to bring the film to the big screen, as we’ll see in the next post.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.